|

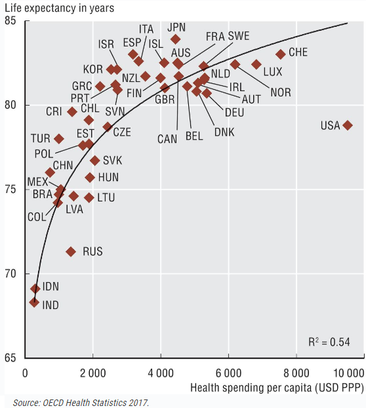

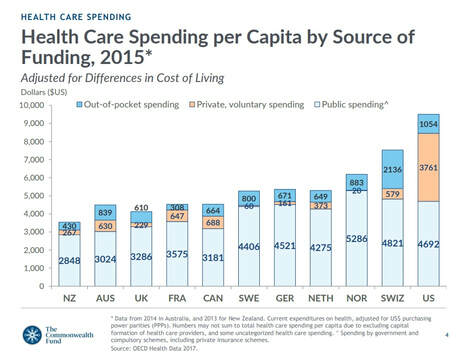

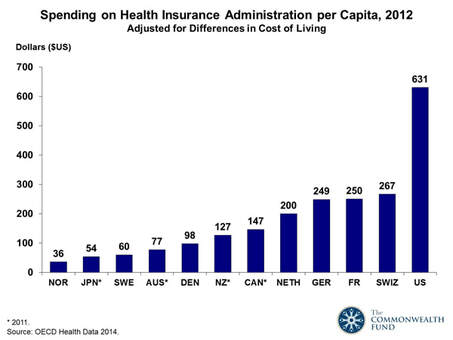

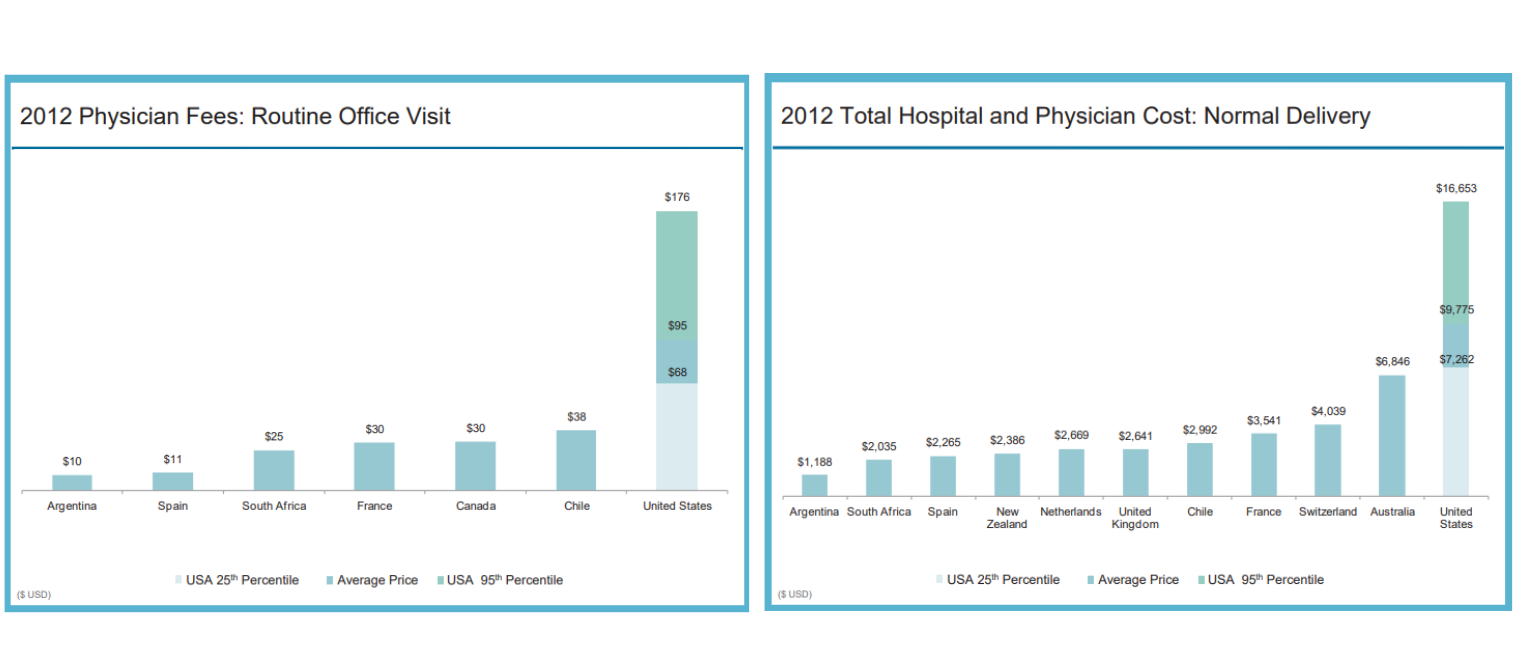

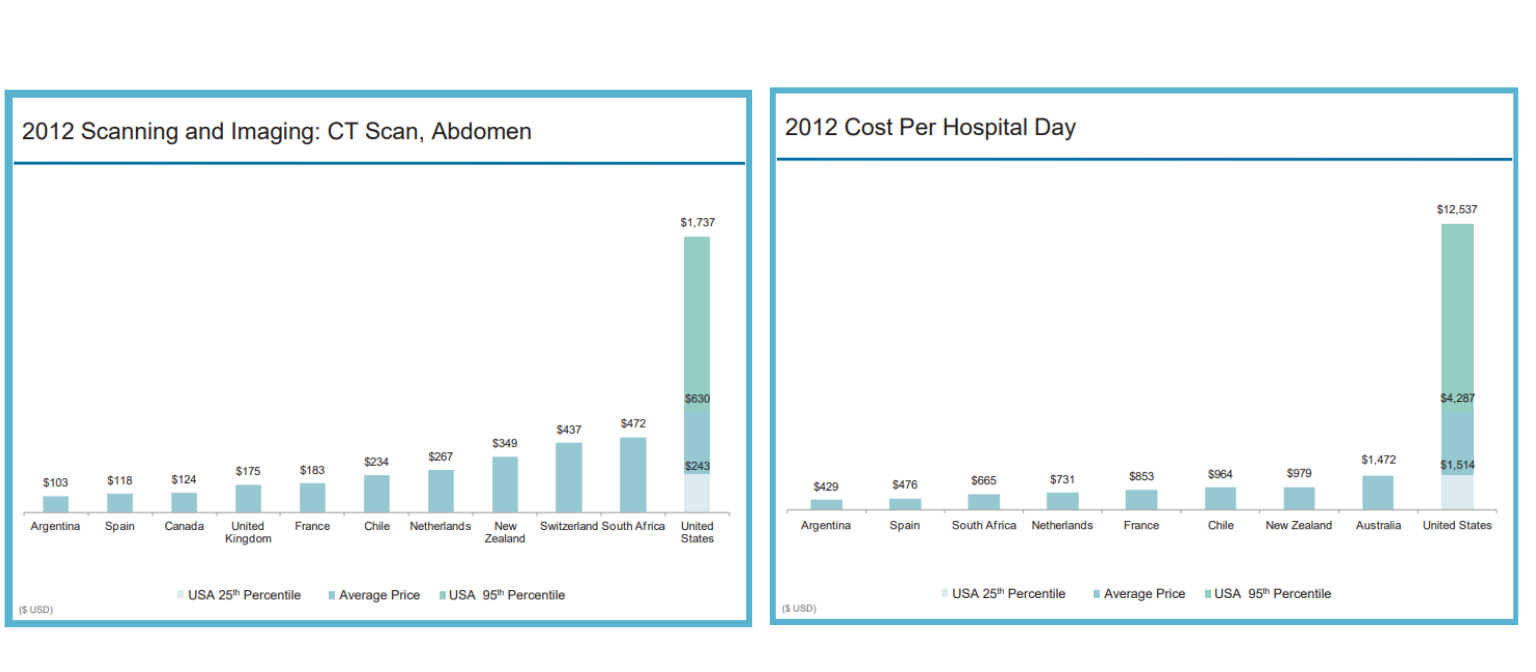

Our United States health system is dysfunctional. It leaves many without coverage, is the most expensive of the world, and drives many others into bankruptcy and poor health outcomes. Our two-tiered system of care maintains access for Americans with comfortable incomes but restricts access for everyone else, noted by Anthony Kovner, PhD as a particularly brutal form of rationing. Majority of us agree that things must change, but we hardly make much progress because we can’t seem to find something that unites us all in our great healthcare debate. I contend that there actually is common ground. Our current President once noted, “Nobody knew healthcare could be so complicated.” However, at its core it really isn’t. An interesting analysis done by the Office for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) showed that there seems to be a connection between life expectancy and how much we spend on healthcare. However, that's not the case for the United States. This may explain why we spend the most over any other comparable country in the world yet our health outcomes are poor and we have a higher level of disease burden than they do. What is it that we are doing differently from these other countries other than leading the world with the highest obesity rates? The most important difference is that we don't have Universal Health Coverage for our citizens and instead treat healthcare as a commodity. We are the only developed country in the world that does this. Universal Health Coverage is one of the most widely shared goals in public health around the globe. While countries do implement different funding mechanisms, they all focus more on who has access to the care. There are two specific instances where the United Nations unanimously declared Universal Health Coverage as a public priority for our world. The first was in 1948 when fifty-three-member countries signed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights agreeing that all member countries would ensure their citizens have the right to adequate health as a public good and not a commodity. Then again with the Sustainable Development Goals of 2015 stating that all UN Member States agree to try and achieve Universal Health Coverage by 2030 urging governments to move towards providing all people with access to affordable, quality health care services as a part of sustaining our human race and planet. Only the developed, industrialized countries (thirty to forty of the world’s two-hundred countries) have established health care systems. These developed countries achieve Universal Health Coverage in several ways, each with its own set of arrangements. None of them trust the free market completely and instead impose regulations like these: insurance companies must accept everyone and cannot make a profit on basic care, everyone is mandated to buy coverage or pay taxes to cover it, the government pays for the poor who cannot, and doctors and hospitals have to accept a standard set of fixed prices. Additionally, not all of the countries do what’s considered socialized medicine, instead many have private doctors and hospitals as a part of the equation. Let me repeat that—single-payer healthcare does not automatically mean socialized medicine. World Health Organization had its 1st Global Symposium on Health System Research in 2010 and had this summary: Out of the countries in their analysis, seventy-five had legislation that provided a mandate for Universal Health Coverage independent of income. The United States was still not one of them. I reached out to a woman who works for the World Health Organization to get some information about accountability towards Universal Health Coverage goals. I was told that the goals are all aspirational and no member country is on the hook for anything; except to their citizens. There will be no sanctions, or the like, for not adhering to these goals. We, as American citizens, have to take it up with our government for not doing so. The United Nations will not. It all begins with the idea that healthcare is a right. This comes naturally for me and I share this sentiment with majority of the population as well. Gallup, The Journal and Pew Research polls showed that most people believe it’s the job of the government to ensure healthcare as a right to their citizens. In other countries healthcare is treated like any other public service similar to how public libraries and police forces are financed by the government and controlled through progressive citizen tax money. Imagine if you had to give a credit card number first before the police comes to your 9-1-1 call. Our right to healthcare is in parallel with the right to public safety or even public road access. Keeping people safe with a police force benefits entire communities. Same goes for keeping people healthy, it affects their entire communities; work, home, neighborhood. This public service philosophy is pretty universal in every other part of the developed world where healthcare is viewed the same as being able to use the library. Often when I speak to people about whether or not healthcare is a right, some say “no” and that it should be paid for on one’s own. With a single-payer health system, everyone pays in their fair share when their taxes are filed. Many of the people who are currently not paying, will be. Simply framed, single-payer means we pay taxes to the government, based on how much we make, and in return we are provided a universal health plan that everyone gets with basics everyone needs. The government then becomes the single-payer in our healthcare. The same goes for how public education is provided; we pay taxes, they plan and manage the system, we show up to school. Our role, other than paying taxes, is to elect people who can rally for our education needs and hope our interests get a say in policy through them. We are the only industrialized country in the world that does not treat healthcare in this fashion. The right to healthcare and expanding coverage to everyone will actually save the health system money because the uninsured are not only an ethical problem but also a fiscal concern. Access to primary care can lower overall health care utilization because increasing access to preventive services will subsequently lower disease rates which cost the system a ton of money. Other benefits manifest as better medication adherence, better management of chronic conditions, reduced reliance on emergency care, and psychological well-being born of knowing one has coverage when getting sick or hurt. When people have access to health care, they live healthier lives and miss work less, allowing them to contribute more to the economy. Norman Daniels, PhD an ethics professor at Harvard University put it this way, "healthcare preserves for people the ability to participate in the political, social, and economic life of society. It sustains them as fully participating citizens." Consider what happens when one cannot get their medications when they have a chronic disease such as high blood pressure or Parkinson’s? Perhaps one could end up in the emergency room, increase disease progression further creating a lower quality of life, have a hard time in their relationships because they are depressed, loose their job because they can’t effectively work, and may end up with an addiction to help ease their pains. This type of life costs more than the one who has access to health coverage and sees their primary care doctor regularly for medication and wellness checks. Economic studies have shown that this is true. One published by the Journal of the American Medical Association found that preventable causes of death are estimated to be responsible for 900,000 deaths annually, which translates to nearly 40% of total yearly mortality in the United States. The Surgeon General estimates that increasing use of preventive services to the recommended levels could save $3.7 billion annually in medical costs. Not only does giving people access to health coverage save the system money with prevention opportunities, it also allows for people to live better quality of life. Don’t we want that for our fellow human beings? I know we want that for ourselves. Another way universal coverage saves costs is that it will reduce uncompensated care, which is a measure of hospital care provided for which no payment was received from the patient or insurer. Since 2000, hospitals of all types have provided more than $620 billion in uncompensated care to their patients ($38 billion in 2017). More importantly is that providers do not bear the full impact of their uncompensated care. Rather, funding is available through a variety of sources to help providers defray the costs associated with it. Kaiser estimated in 2013 that $53.3 billion of taxpayer money was used to help providers offset uncompensated care costs. We are already paying for the uninsured through uncompensated care provider tax-relief. These are our public dollars. Why don’t we put that $53 billion into the system and expand coverage to keep people healthier, instead of paying off the consequences of the uninsured through tax relief to providers? Even more interesting—the following study by The Commonwealth Fund shows that we are already paying what other countries pay for and Universal Health Coverage—except we don't have it. Instead, it shows that our current privatized and fragmented healthcare system costs more than public healthcare for other countries around the world. I must repeat this—we are already paying for the cost of Universal Health Care—and then some. There are a lot of healthcare dollars in our system, they are just used ineffectively and in the wrong places. Beyond the examples above, the Institute of Medicine estimates that we waste a half-trillion dollars annually through inefficiency. The United States is unlike every other country because it maintains so many separate systems for separate classes of people. All other developed countries have settled on one model for everybody. This is much simpler than our system; it’s fairer and cheaper, too. Physicians for a National Health Program says that when it comes to treating veterans, we’re Britain or Cuba. For Americans over the age of 65 on Medicare, we’re Canada. For working Americans who get insurance on the job, we’re Germany. For the 10-15% of the population who have no health insurance, the United States is Cambodia or Burkina Faso or rural India, with access to a doctor available if you can pay the bill out-of-pocket at the time of treatment or you go without. There are hidden costs of our system’s complexity; fifty different sets of State insurance regulations for managing Medicaid, there are over eight-hundred different health insurance companies, we all pay different premiums, every employer is a different large group, our charges for services all differ based on provider groups and insurance company. This multi-payer way of financing care directly creates an administrative burden. BMC Health Services Research estimated that moving to a single-payer healthcare system can reduce our administrative expenditures by 80% and that a simplified financing system would result cost savings exceeding $350 billion annually. Combine all of that with the fact that we lose tens of billions of dollars to fraud a year that is born from this very fragmented and complex billing system. Further, the foundation for these administrative burdens all stem from the fact that we uniquely allow our health system’s organizations to profit. As a result, we pay premiums that are inflated with insurance marketing and advertising costs as well as multi-million-dollar compensation for its executives. This is why the National Health Expenditure analysis noted that private health insurance plans spend 11.7% of premiums and administrative costs versus 6.3% spent by public health programs. Our high administration costs and system complexity have directly added to the cost of our health services. In 2012 Harvard published an analysis by the International Federation of Health Plans that showed variations in hospital price by country. The results are shocking to say the least with the United States having a significant increase in cost for every single measure studied. Did you know that many of us are paying two-to-four times as much than other countries for procedures? This is because every other country has some kind of government mechanism built in to control prices. We negotiate when we buy cars, we get upset when cable costs too much, yet in healthcare we don't question these costs. This is partially due to the fact that we don't have a clue about costs because we are not the direct payer, an insurance company handles it for us. However, these are the prices we are indirectly paying, and comparable countries are providing the same services for a fraction of the price under some form of universal health coverage. The U.S. Census notes that 8.8% of the population, or 28.5 million people, did not have health insurance at any point during 2017, which is the highest rate than any other developed country in world. Who are these people? Majority of them live in Texas and other parts of the south, between the age of 19 and 64, make less than $25,000 a year, is either black or Hispanic, and live in poverty of some kind. It’s very clear the disparities of who has access to health coverage and who does not. I won’t go into the immoral nature of this now, but I want to make a point that deep racial and ethnic disparities remain when it comes to health coverage and equity. The refusal of nearly twenty states to expand Medicaid, particularly in the South, has left hundreds of thousands of Americans with these demographics uninsured.

In Germany their health system is considered multi-payer because they use an employer-based system similar to ours. However, they are able to achieve Universal Health Coverage since three distinctions are upheld: tight regulation gives government much of the cost-control clout that the single-payer provides, health insurance plans have to cover everybody and cannot make a profit, and those who do not work and cannot afford to pay out-of-pocket receive public assistance to pay their premiums. Another big distinction Germany has is their cultural affirmation of safety-nets. They believe strongly, as a part of their culture, to take care of the disadvantaged because they acknowledge and accept the fact that anyone can fall into a disadvantaged state at any time. Professor Karl Lauterbach, a member of the German parliament, describes it as "a system where the rich pay for the poor and where the ill are covered by the healthy. It’s a social support system that is highly accepted by the population." They don't argue politically over whether or not to include a safety net, because they accept its necessity and that healthcare is a right to all. It is no surprise then that Germany has a higher life expectancy and lower infant mortality rate than we do. Single-payer, government-sponsored plans not only promise universal access, but also basic and essential benefits for every American. Some ways of approaching this can include a lot of government control, others can still include private insurers. The unfortunate circumstance in the great American healthcare debate is that our policymakers are fighting about how to take away care from the poor because they can’t pay for it. Instead, the overall goal should be to increase coverage and make it a public right for everyone. We can debate about how we do it during elections and in congressional conversations. Until then, I am calling for all politicians who are representing the people of the United States this 2020 election season to take a unified and bi-partisan approach to Universal Health Coverage and debate about the funding mechanisms and how we should do it, instead of fighting about whether or not we should. This is one opportunity where we can actually unite and get something meaningful done. Our elected policymakers must decide how much they value investments in our personal and community health. Remember, we are not isolated beings, we live in society with others, therefore an investment in one, is an investment in all. The closest thing to single-payer already working and established in the United States is Medicare, which is where the concept of Medicare-for-all comes from. The infrastructure is already built so it saves time and subsequently our taxpayer dollars. Medicare was established in 1965 to provide health insurance to all people age sixty-five and older, regardless of income or medical history. This is in direct alignment with the goal of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights of 1948. Since then, all other developed nations of the world, besides us, have implemented some form of Universal Healthcare for all of their citizens. Instead the United States only declared this human right for anyone over the age of sixty-five. No one else. The program was expanded many times in the past to include people under age sixty-five; those with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in 1972 and in 2001 for those with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease). We seem capable of expanding coverage for those who are really sick, but not those who are poor. Medicare eligibility can further be expanded to help all people. Everyone who is working already pays for Medicare in their payroll taxes. This can be changed to be paid once a year during tax time. Options are available. It is often argued that Medicare-for-all would make us bankrupt and broke. What people often are missing is that although taxes will increase, our out-of-pocket monthly premiums will be eliminated. Forbes reports that “for the country as a whole this would largely be a financial wash.” This is in addition to what was noted earlier as well; we are already paying a whole lot more than other countries are paying for universal coverage and wasting money away too in efficiencies. Some form of Medicare expansion will not bankrupt us. The money to do it is already in the system. Yes, it will stop corporations from profiting off of us, which will make them upset of course, and as a result are the biggest opponents of Medicare expansions. The trade-offs of Medicare-for-all will take time, but what will happen with better efficiencies and usage of taxpayer dollars. I'm already paying $700 a month for a health policy through my employer that gives it to Aetna for me. I'd rather send my money to a federal system that will not profit off of me. Single-payer systems like Medicare-for-all will not be perfect, but will solve some of our fiscal and ethical dilemmas because it would be controlled by a government entity with public oversight and not a giant corporation that does not have our best interests in mind. Isn’t that the purpose of electing our politicians and having a government—so they can represent our best interests? At least that was the point of our founding Constitution. We could also keep private insurers and expand Medicare to all through the use of Medicare Advantage plans which are already developed, effective, and working. These are private insurance plans offered to Medicare beneficiaries that include additional coverage not covered by traditional Medicare. Private insurance plans that offer Medicare Advantage must compete with one another for Medicare's business which takes a market-oriented approach to competition and pricing. The Affordable Care Act put some regulations in place that required private insurance companies offering these plans to follow in order to help contain costs and maintain solvency—all in the interest of its beneficiaries (all of us who pay into the system for many years). Medicare Advantage plans are the managed care of Medicaid, except with regulation. State Medicaid managed care plans are not Federally regulated, which is why they are very inefficient, expensive, and full of moral abuses. A study published in Health Affairs found that Medicare Advantage plans, with the Federal regulation it has, costs less and delivers higher quality care than traditional Medicare. We can work out a deal with private insurance companies that wins for all stakeholders. Additionally, we get more choice, get the right to health, get to be one of several hundred million potential voters to help shape its structure, and become the true customer of American healthcare. This last component is extremely important because anyone under the age of sixty-five that has private health insurance is not the true customer in American healthcare. Large and small group employers are. Insurance companies don't sell to us, their plans are developed and designed and marketed to the needs of employers. Not consumers. Medicare Advantage plans are the only health plans, other than ones on the State Marketplaces and sold through brokers, that are targeted and developed for the individual. In an era of disruption, innovation, and entrepreneurship, health plans that are focused on individuals will evolve and be designed to accommodate individual needs. What we demand and want in healthcare will naturally arise from consumer demand when the individual is the customer. As health plans get disrupted, so will our providers who will regain autonomy and provide services for us that are designed to work the best for us, not designed so they are reimbursed the most by insurance. Expanding Medicaid coverage works too, but there are too many problems with the system because of its complexity between Federal, State, and managed care. If this complex system is simplified by getting rid of State regulation and moving toward standardized Federal regulation, then expanding Medicaid coverage through various programs such as buy-ins can work in the same fashion. But why keep young and the old citizens separate? Why have Medicaid for under sixty-five and Medicare for over sixty-five? It actually makes more sense to combine the two into one system for all the complexity reasons stated earlier, but also because it allows the older to spread their risk amongst everyone, including the much, much younger. In the same fashion as how large employer group plans are cheaper because they can spread the risk more, we can spread the risk amongst everyone in the country. Instead, we currently spread the risk amongst the poor (Medicaid) and the elderly (Medicare) in separate risk pools and wonder why we can’t control costs? I want to end by briefly touching upon the understanding that single-payer or Medicare-for-all programs will force physicians and other providers to take the biggest hit initially. However, providers have directly influenced our current situation and how we reimburse them needs to evolve. The fee-for-service reimbursement mechanism has pushed providers into a quantity-based mindset, which is why they see us for the short periods of times that they do. The Physicians Foundation surveyed U.S. doctors and found that about 40% see eleven to twenty patients per day and 27% see twenty to thirty a day. A forum of nurses note that they attend to an average of eighteen colonoscopies a day. We will no doubt have better health outcomes if our providers spend more quality time and interest in our health, instead of viewing us as items on a factory belt. Currently the system is not set up for the right incentives. We often look to doctors as if they are god's, without fault, but there is a reason why medical mistakes persists as the number three killer in the US—third only to heart disease and cancer. Providers need a serious reality check, and perhaps taking smaller salaries because what they provide is a public good and right to humans, should be considered. Absolutely, we should reform medical school tuition to help with this situation, but doctors have a duty to their fellow humans and maybe we need more ethical doctors who follow the oaths they take in medical school. Physicians that have high quality scores and do well with their patients, just like any other business, will succeed and do just fine. We want the low-performing doctors that have high complication rates to stop getting paid the same as doctors with high quality scores, and instead, go out of business. Remember the old adage “What do you call the person that graduates lowest in their class from Medical School? Doctor.” We as consumers are the only ones who can provide the guidance to our legislators on how to change the approach. Providers have been insulated from this market-based competition, and maybe that's exactly what they need. Change is what we need. Let’s start asking for it. Begin to take power back and become an informed health consumer. Share this with somebody you care about.

1 Comment

|

Kat LahrResearcher, Writer, Educator, Reformer & Believer of Health Care as a Right Archives

April 2020

|

|

CREATING AWARENESS IN

HEALTH CONSUMERS |

TC Publishing |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed