Addressing Health Injustice in the United States Through Accountability & Citizen Participation4/9/2020 PROLOGUE (COVID-19 update) I wrote this post before the coronavirus outbreak and I wanted to add some additional thoughts about this global pandemic as my words below are even more important and evident now. The novel coronavirus affects everyone, but some groups suffer more, such as marginalized populations who live in poverty and those who suffer due to health inequities. Coronavirus is exposing all of the weaknesses in the U.S. health system and has shown that the nation was less prepared for a pandemic than countries with universal health systems due to lack of universally accessible screening and the uninsured or underinsured still priced out of care. Those losing their jobs due to the economic shutdown will subsequently lose their health insurance coverage, showing us is just how unreliable the employer-based framework really is. In the interim, U.S. legislators have agreed to make American healthcare more like other nations by making COVID-19 treatment free or low-cost at the point of service, either by having the government cover the cost or by mandating private health insurers to cover services related to the pandemic. This helps bridge the insurance coverage gap for those who do not have private health insurance or qualify for Medicaid and was a pivotal and encouraging development. But this would have been far more impactful if it was already in place, removing any delay in care to anyone in an effort to control the spread. Amid this crisis, millions of Americans are now demanding that we have a government that works for all, making a stronger case for universal health coverage. As a result, it’s important that local and global public health leaders continue to pursue health equity during the outbreak response, aiming to protect vulnerable and marginalized communities from COVID-19. Even though Eleanor Roosevelt, human rights champion and First Lady of the United States, was Chair of the United Nations Commission that wrote the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, the U.S. still stands alone within the developed world in not making healthcare a basic human right to all of its citizens, without a mandate to provide universal health coverage (UHC) independent of income. This means that healthcare is, instead, treated as a commodity for most people, something that is bought, considered a privilege and a benefit. Recently, all United Nations member states adopted the Sustainable Development Goals of 2015, agreeing to try to achieve UHC by 2030, urging governments to move toward providing all people with access to affordable, quality healthcare services as a part of sustaining our human race and planet. Although these goals are a beautiful example of a universal call to action to protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity by 2030, unfortunately, accountability is lacking. The goals are all aspirational. There will be no sanctions or the like on the U.S. for not adhering to these goals. Americans have to take it up with their government if it does not do so. The United Nations will not.

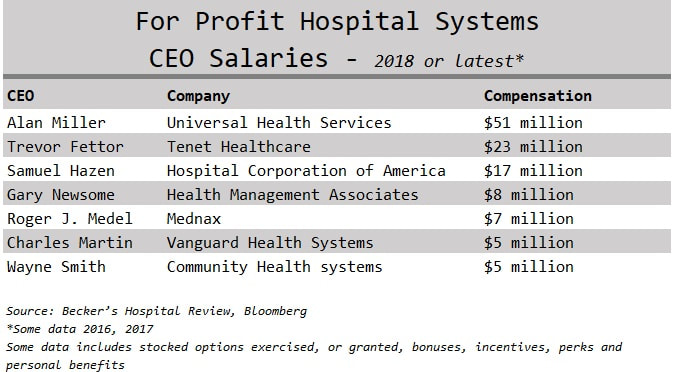

While states are formally accountable to their populations, people often have limited meaningful opportunities to hold their governments accountable. However, I firmly believe in the power of the people and their voting rights to help provide pressure for domestic accountability towards UHC if they are supported by a treaty such as the Framework Convention on Global Health (FCGH). This treaty is aimed at addressing the shortcomings in implementing the right to health, including through binding standards requiring accountability and enforceability. The FCGH Alliance is in the process of articulating these standards. These binding remedies would hold states accountable for health justice violations and would advance health equity by better ensuring that those responsible for the abuses answer for their actions. One of the key principles that the FCGH Alliance proposes for the Framework Convention on Global Health centers around empowering people to claim and enforce their right to health. However, this all begins with education and being informed. Yet governments, especially in the U.S., often fail to adequately equip users with a good understanding of the health system. Information makes one liberated and is the foundation of progress. If Americans become knowledgeable, they have power, and that power can impact their healthcare system, enabling health to become a right embodied in U.S. law, and changing the status quo in which powerful interests, whether wealthy segments of the population who want to keep taxes low or corporations that prioritize their profits, keep the commodity-based system intact. The recent U.S. comprehensive health law, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010, helped to increase access, decrease costs, and raise quality standards. However, the Act lacks any provisions regarding the duty of the government to develop capacity in empowering people to claim and enforce their right to health. The ACA does include transparency of claim denials by insurers, costs of services and quality scores by providers, but is mute on principles that empower people to demand accountability from the government itself. The FCGH would seek to improve national accountability to health commitments, including by promoting the principle of people’s meaningful participation in developing, monitoring, and evaluating laws, policies, and programs that may impact their right to health. A genuine opportunity to influence decisions related to their health equity must be available locally, regionally, and nationally for everyday citizens, non-citizens, and civil society organizations. For example, a discussion draft of the FCGH includes a section on Participation that could contribute to accomplishing this. Other organizations, such as the National Issues Forum (NIF) can partner with and develop local town and district health committees and working groups that include members of the public. There are plenty of options available that elected U.S. public representatives can utilize to empower their constituents. However, provisions in federal health legislation must be developed to enforce this participation, such as requiring a certain number or percentage of people from various jurisdiction to participate before laws affecting the right to can become enacted or providing funding to enable these participation opportunities. An FCGH can assist and advise on the best way to bring about this accountability and participation for each country, in this case, the United States. But for a treaty like the FCGH to be successful in the United States, Americans must be informed enough to accept it and put pressure on their elected representatives to support it. I see the FCGH Alliance as a partnership that can help Americans become more educated on health policy and their rights and cause this pressure to mount. In an effort to help move toward health equity in the U.S. through getting information to the American people, I have recently published a book to help close the gap of the health system illiteracy. This book aims to provide a snapshot of the core dialogue taking place in our healthcare system and provides a moral argument for health equity. I provide evidence showing how health inequity is the basis of the United States health system’s problems and the need for accountability and citizen participation as a requirement for any lasting change to happen. My book aims to provide a path for social empowerment for the often powerless American healthcare consumer. The balance of profit and social justice is a true dilemma in the U.S. healthcare system and leads to a level of inequality that is unconscionable. Its commodity-based system forces leaders of health organizations to be motivated by money, deterring them from the mission of caring for the sick and injured, promoting prevention, and keeping people healthy. For example, healthcare is unaffordable and inaccessible for many, yet executives of these companies take home salaries at the amount of millions of dollars. And many legislators make decisions that decrease coverage instead of increasing it, making healthcare more expensive for people, even while high compensation for executives continues. This commodity-based system has put incentives in the wrong places, compromising health justice. Implementing an FCGH in the U.S. would include catalyzing a domestic health financing and accountability framework that would protect limited resources for healthcare by demanding increased transparency and combating corruption through pathways such as improved resource allocation disclosure requirements and better enforcement of standards to ensure accountability for any misuse of public health resources. Moving to a system where the incentives change and the priorities shift to include everyone, will move us towards health justice. What a government prioritizes and spends its money on defines what is important to it, and extending access to quality healthcare to everyone has never been made a bi-partisan priority in the United States. One of the biggest issues in the U.S. healthcare system is not the lack of money for universal health coverage but how limited healthcare dollars are being spent. The U.S. is already paying what other countries pay for universal health coverage—except the U.S. doesn’t have it. Instead its current largely privatized and fragmented commodity-based healthcare system costs more than public healthcare for other countries around the world. It bears repeating: the U.S. is already paying for the cost of Universal Health Care and then some. An FCGH would provide legal backing in negotiating laws and policies that provide non-discriminatory healthcare to all, a long-standing global public health goal, and help elected public officials push back against policies that do the opposite through clear requirements for equitable distribution. Society suffers injustice when not everyone gets to share in the benefits and when distributions of resources are not equal. When health equity is compromised, health disparities shade society with injustice, which is the unfortunate reality in the United States. For example, 21% of non-elderly Hispanic people are uninsured, while only 8% of whites are. Additionally, babies born to black women with professional degrees are about three times more likely to die than babies born to white women with only a high school diploma or its equivalent. The FCGH shall be the foundation upon which marginalized communities in the U.S., such as people of color and low-income individuals, who have long been discriminated against and excluded from decision-making, will be ensured of avenues to demand their right to health and justice. No matter what our circumstance, environment, or influence, we are human, and basic rights for everyone in all positions of society must be observed to truly live in a moral, ethical, and just society. I am encouraged by the mission of the FCGH Alliance and its vision towards a more just society that ensures the right to health for all people by addressing health injustice through governmental accountability and citizen awareness and participation.

1 Comment

Photo by Tirachard Kumtanom from Pexels “The improvement of medicine would eventually prolong human life, but improvement of social conditions could achieve this result even more rapidly and successfully.” - Rudolf Virchow, German Physician, 1879

A major public health milestone was achieved in The United States in 1985 when the Department of Health and Human Services published the Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health. This marked the inception of a new era in acknowledging minority health issues. While action has been taken nationally since to address the issues noted in the report, health inequity persists and remains a distinction within American society. The World Health Organization defines health inequities as systematic differences in the health status of different population groups. Society suffers health inequity when not everyone gets to share in the opportunities and when distributions of resources are not equal—a failure of distributive justice. These inequities have significant social and economic costs both to individuals and their communities. Achieving health equity means that everyone has the basics to be as healthy as possible. There is substantial evidence that social factors, including education, gender, ethnicity, employment status, and income level have significant influence on a person’s health. This is why health equity is a multiple-industry concern. There are a multitude of benefits gained from investment towards health equity, including reducing suicide rates among the transgendered, lowered readmissions, improved health outcomes, and reduction of health disparities to name just a few. Health equity is not only a moral issue, but also an economic one as well. Economic Load Wise policymakers, medical centers, insurers, and providers have realized that health equity affects the bottom line. A study published in 2018 by the Connecticut Department of Public Health noted that “race and ethnicity were associated with higher hospital charges and estimated excess charges (compared to white residents) of Black residents was over $1.2 billion and $378 million for Hispanic residents.” Higher utilization was found to be a prevention failure because of undiagnosed diseases such as diabetes and heart disease. Another study in the International Journal of Health Services published in 2011 found that nationally “eliminating health disparities for minorities would have reduced direct medical care expenditures by about $230 billion and indirect costs associated with illness and premature death by more than $1 trillion for the years 2003-2006.” Specifically for health insurers, racial health disparities alone were estimated to cost the U.S. $337 billion between 2009 and 2018 as reported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. These are limited healthcare dollars, wasted away. Numerous measurements were used for estimating the economic impact in these studies include, but not limited to, the following:

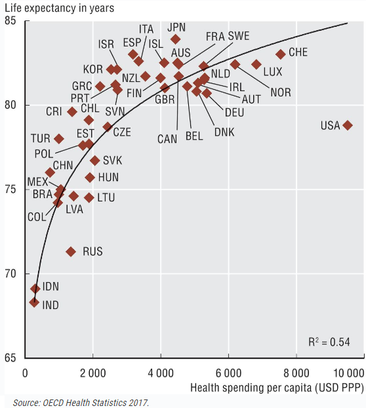

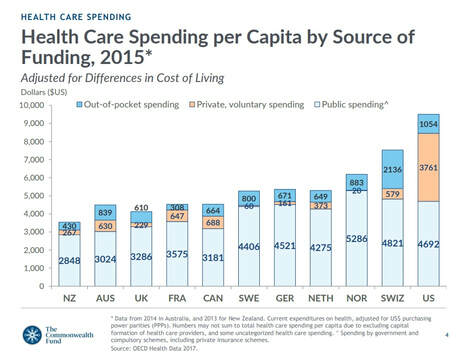

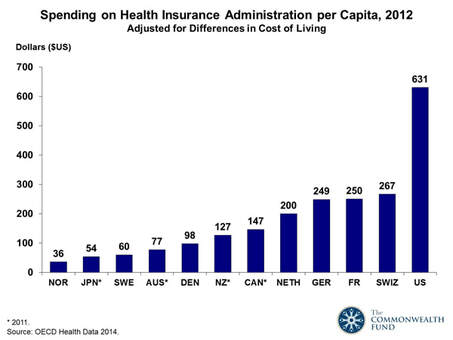

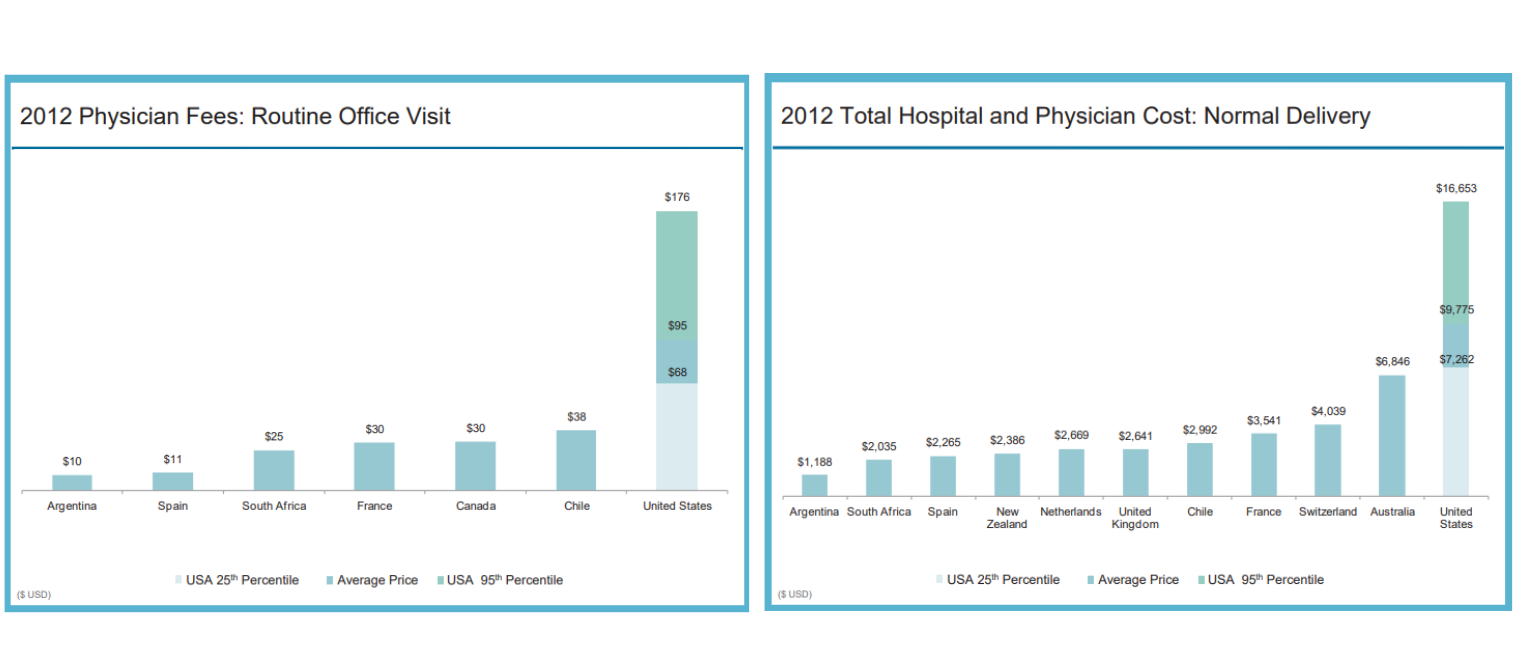

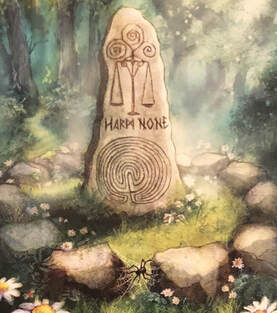

Investing in disease prevention not only saves lives but yields a significant return on investment. For example, increasing access to arthritis treatment for 10,000 people, reducing their pain by 18% and increasing their productivity and quality of life, could save more than $2.5 million according to the Alliance for Health Reform. There are system-wide impacts as well. Increased healthcare costs erode company profits leaving less money to invest in equipment or expansion, and force companies to increase prices for their products. GM estimated that providing health insurance for its employees added $1,400 to the cost of every vehicle built in the U.S. in 2004. Moral & Just Society Award-winning 20th century philosopher John Rawls was interested in what makes a just and moral society. He formulated a hypothetical theory where people are equal to each other, and all humans have worth in the Original Position, and if we take a Veil of Ignorance with each other, a social contract would develop that secures basic rights for everyone and protects those in all positions of society. His theory goes on to say that the advantaged have a responsibility to the disadvantaged. Those that are disadvantaged could include those in poverty, those with chronic diseases that affect quality of life, the disabled, etc. Therefore, in the end, it is in our ultimate best interest to do this, because everyone has the potential to be in the lesser position (loss of job, health, etc.) Rawl developed these theories during the Great Depression, when people's lives regularly changed overnight. John Rawls said, “A just society is a society that if you knew everything about it, you'd be willing to enter it in a random place.” Consider that powerful thought: are you willing to be born into a low-income, Black family in Philadelphia or Chicago? Statistically, this population has the highest rate of health disparities in the country, and as a result, end up in unhealthy situations that produces another statistic: highest homicide rate in the country. At the core of Rawls theory is that no matter what our circumstance, environment, or influence, we are human, and all human interests must be observed to truly live in a moral, ethical, and just society. An example of this is the immoral nature of deep racial and ethnic disparities that remain when it comes to health coverage and equity. The refusal of nearly 20 states to expand Medicaid, particularly in the south, has left hundreds of thousands of Americans with these demographics uninsured. Many health organizations are paying attention to health equity and they are doing so not just because it is the right thing to do, but because the financial incentives are increasingly aligning. Institutions that do not respect the importance of achieving health equity in their systems and communities will struggle as our country moves ahead toward a health system that is more patient-centered and accessible. ------ Kat is an award-winning writer, educator, reformer, health advocate, and believer of healthcare as a human right. She believes that most of us aren't comfortable watching people suffer when help is available, and when we assist each other in surviving, everyone benefits. She advocates for awareness, transparency, and a person’s right to know. Information about her most recent book can be found at www.toerrishealthcare.com/book-1. Our United States health system is dysfunctional. It leaves many without coverage, is the most expensive of the world, and drives many others into bankruptcy and poor health outcomes. Our two-tiered system of care maintains access for Americans with comfortable incomes but restricts access for everyone else, noted by Anthony Kovner, PhD as a particularly brutal form of rationing. Majority of us agree that things must change, but we hardly make much progress because we can’t seem to find something that unites us all in our great healthcare debate. I contend that there actually is common ground. Our current President once noted, “Nobody knew healthcare could be so complicated.” However, at its core it really isn’t. An interesting analysis done by the Office for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) showed that there seems to be a connection between life expectancy and how much we spend on healthcare. However, that's not the case for the United States. This may explain why we spend the most over any other comparable country in the world yet our health outcomes are poor and we have a higher level of disease burden than they do. What is it that we are doing differently from these other countries other than leading the world with the highest obesity rates? The most important difference is that we don't have Universal Health Coverage for our citizens and instead treat healthcare as a commodity. We are the only developed country in the world that does this. Universal Health Coverage is one of the most widely shared goals in public health around the globe. While countries do implement different funding mechanisms, they all focus more on who has access to the care. There are two specific instances where the United Nations unanimously declared Universal Health Coverage as a public priority for our world. The first was in 1948 when fifty-three-member countries signed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights agreeing that all member countries would ensure their citizens have the right to adequate health as a public good and not a commodity. Then again with the Sustainable Development Goals of 2015 stating that all UN Member States agree to try and achieve Universal Health Coverage by 2030 urging governments to move towards providing all people with access to affordable, quality health care services as a part of sustaining our human race and planet. Only the developed, industrialized countries (thirty to forty of the world’s two-hundred countries) have established health care systems. These developed countries achieve Universal Health Coverage in several ways, each with its own set of arrangements. None of them trust the free market completely and instead impose regulations like these: insurance companies must accept everyone and cannot make a profit on basic care, everyone is mandated to buy coverage or pay taxes to cover it, the government pays for the poor who cannot, and doctors and hospitals have to accept a standard set of fixed prices. Additionally, not all of the countries do what’s considered socialized medicine, instead many have private doctors and hospitals as a part of the equation. Let me repeat that—single-payer healthcare does not automatically mean socialized medicine. World Health Organization had its 1st Global Symposium on Health System Research in 2010 and had this summary: Out of the countries in their analysis, seventy-five had legislation that provided a mandate for Universal Health Coverage independent of income. The United States was still not one of them. I reached out to a woman who works for the World Health Organization to get some information about accountability towards Universal Health Coverage goals. I was told that the goals are all aspirational and no member country is on the hook for anything; except to their citizens. There will be no sanctions, or the like, for not adhering to these goals. We, as American citizens, have to take it up with our government for not doing so. The United Nations will not. It all begins with the idea that healthcare is a right. This comes naturally for me and I share this sentiment with majority of the population as well. Gallup, The Journal and Pew Research polls showed that most people believe it’s the job of the government to ensure healthcare as a right to their citizens. In other countries healthcare is treated like any other public service similar to how public libraries and police forces are financed by the government and controlled through progressive citizen tax money. Imagine if you had to give a credit card number first before the police comes to your 9-1-1 call. Our right to healthcare is in parallel with the right to public safety or even public road access. Keeping people safe with a police force benefits entire communities. Same goes for keeping people healthy, it affects their entire communities; work, home, neighborhood. This public service philosophy is pretty universal in every other part of the developed world where healthcare is viewed the same as being able to use the library. Often when I speak to people about whether or not healthcare is a right, some say “no” and that it should be paid for on one’s own. With a single-payer health system, everyone pays in their fair share when their taxes are filed. Many of the people who are currently not paying, will be. Simply framed, single-payer means we pay taxes to the government, based on how much we make, and in return we are provided a universal health plan that everyone gets with basics everyone needs. The government then becomes the single-payer in our healthcare. The same goes for how public education is provided; we pay taxes, they plan and manage the system, we show up to school. Our role, other than paying taxes, is to elect people who can rally for our education needs and hope our interests get a say in policy through them. We are the only industrialized country in the world that does not treat healthcare in this fashion. The right to healthcare and expanding coverage to everyone will actually save the health system money because the uninsured are not only an ethical problem but also a fiscal concern. Access to primary care can lower overall health care utilization because increasing access to preventive services will subsequently lower disease rates which cost the system a ton of money. Other benefits manifest as better medication adherence, better management of chronic conditions, reduced reliance on emergency care, and psychological well-being born of knowing one has coverage when getting sick or hurt. When people have access to health care, they live healthier lives and miss work less, allowing them to contribute more to the economy. Norman Daniels, PhD an ethics professor at Harvard University put it this way, "healthcare preserves for people the ability to participate in the political, social, and economic life of society. It sustains them as fully participating citizens." Consider what happens when one cannot get their medications when they have a chronic disease such as high blood pressure or Parkinson’s? Perhaps one could end up in the emergency room, increase disease progression further creating a lower quality of life, have a hard time in their relationships because they are depressed, loose their job because they can’t effectively work, and may end up with an addiction to help ease their pains. This type of life costs more than the one who has access to health coverage and sees their primary care doctor regularly for medication and wellness checks. Economic studies have shown that this is true. One published by the Journal of the American Medical Association found that preventable causes of death are estimated to be responsible for 900,000 deaths annually, which translates to nearly 40% of total yearly mortality in the United States. The Surgeon General estimates that increasing use of preventive services to the recommended levels could save $3.7 billion annually in medical costs. Not only does giving people access to health coverage save the system money with prevention opportunities, it also allows for people to live better quality of life. Don’t we want that for our fellow human beings? I know we want that for ourselves. Another way universal coverage saves costs is that it will reduce uncompensated care, which is a measure of hospital care provided for which no payment was received from the patient or insurer. Since 2000, hospitals of all types have provided more than $620 billion in uncompensated care to their patients ($38 billion in 2017). More importantly is that providers do not bear the full impact of their uncompensated care. Rather, funding is available through a variety of sources to help providers defray the costs associated with it. Kaiser estimated in 2013 that $53.3 billion of taxpayer money was used to help providers offset uncompensated care costs. We are already paying for the uninsured through uncompensated care provider tax-relief. These are our public dollars. Why don’t we put that $53 billion into the system and expand coverage to keep people healthier, instead of paying off the consequences of the uninsured through tax relief to providers? Even more interesting—the following study by The Commonwealth Fund shows that we are already paying what other countries pay for and Universal Health Coverage—except we don't have it. Instead, it shows that our current privatized and fragmented healthcare system costs more than public healthcare for other countries around the world. I must repeat this—we are already paying for the cost of Universal Health Care—and then some. There are a lot of healthcare dollars in our system, they are just used ineffectively and in the wrong places. Beyond the examples above, the Institute of Medicine estimates that we waste a half-trillion dollars annually through inefficiency. The United States is unlike every other country because it maintains so many separate systems for separate classes of people. All other developed countries have settled on one model for everybody. This is much simpler than our system; it’s fairer and cheaper, too. Physicians for a National Health Program says that when it comes to treating veterans, we’re Britain or Cuba. For Americans over the age of 65 on Medicare, we’re Canada. For working Americans who get insurance on the job, we’re Germany. For the 10-15% of the population who have no health insurance, the United States is Cambodia or Burkina Faso or rural India, with access to a doctor available if you can pay the bill out-of-pocket at the time of treatment or you go without. There are hidden costs of our system’s complexity; fifty different sets of State insurance regulations for managing Medicaid, there are over eight-hundred different health insurance companies, we all pay different premiums, every employer is a different large group, our charges for services all differ based on provider groups and insurance company. This multi-payer way of financing care directly creates an administrative burden. BMC Health Services Research estimated that moving to a single-payer healthcare system can reduce our administrative expenditures by 80% and that a simplified financing system would result cost savings exceeding $350 billion annually. Combine all of that with the fact that we lose tens of billions of dollars to fraud a year that is born from this very fragmented and complex billing system. Further, the foundation for these administrative burdens all stem from the fact that we uniquely allow our health system’s organizations to profit. As a result, we pay premiums that are inflated with insurance marketing and advertising costs as well as multi-million-dollar compensation for its executives. This is why the National Health Expenditure analysis noted that private health insurance plans spend 11.7% of premiums and administrative costs versus 6.3% spent by public health programs. Our high administration costs and system complexity have directly added to the cost of our health services. In 2012 Harvard published an analysis by the International Federation of Health Plans that showed variations in hospital price by country. The results are shocking to say the least with the United States having a significant increase in cost for every single measure studied. Did you know that many of us are paying two-to-four times as much than other countries for procedures? This is because every other country has some kind of government mechanism built in to control prices. We negotiate when we buy cars, we get upset when cable costs too much, yet in healthcare we don't question these costs. This is partially due to the fact that we don't have a clue about costs because we are not the direct payer, an insurance company handles it for us. However, these are the prices we are indirectly paying, and comparable countries are providing the same services for a fraction of the price under some form of universal health coverage. The U.S. Census notes that 8.8% of the population, or 28.5 million people, did not have health insurance at any point during 2017, which is the highest rate than any other developed country in world. Who are these people? Majority of them live in Texas and other parts of the south, between the age of 19 and 64, make less than $25,000 a year, is either black or Hispanic, and live in poverty of some kind. It’s very clear the disparities of who has access to health coverage and who does not. I won’t go into the immoral nature of this now, but I want to make a point that deep racial and ethnic disparities remain when it comes to health coverage and equity. The refusal of nearly twenty states to expand Medicaid, particularly in the South, has left hundreds of thousands of Americans with these demographics uninsured.

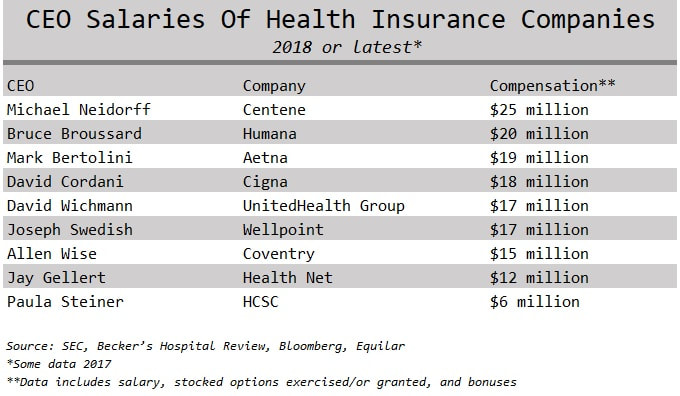

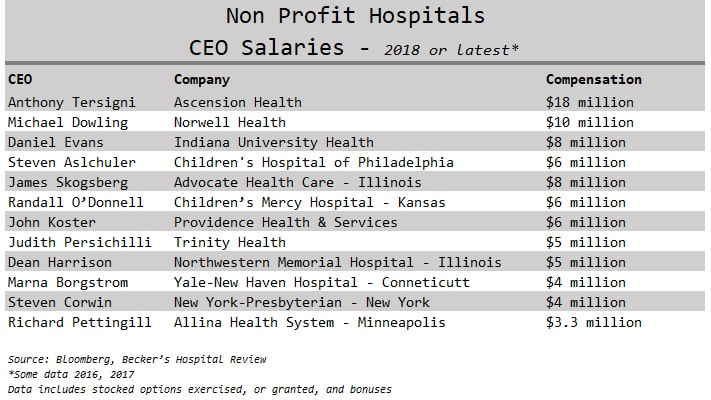

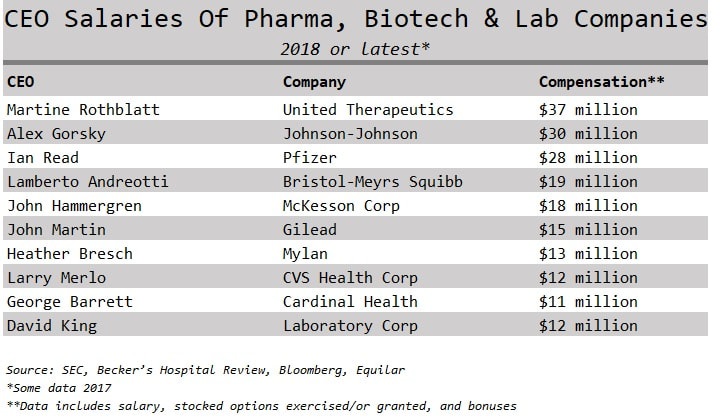

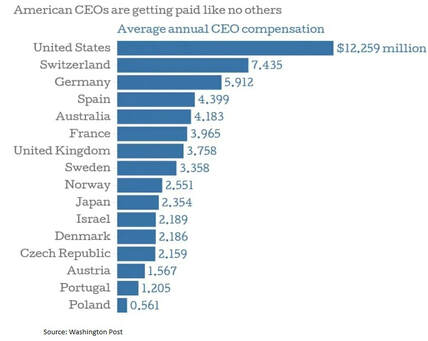

In Germany their health system is considered multi-payer because they use an employer-based system similar to ours. However, they are able to achieve Universal Health Coverage since three distinctions are upheld: tight regulation gives government much of the cost-control clout that the single-payer provides, health insurance plans have to cover everybody and cannot make a profit, and those who do not work and cannot afford to pay out-of-pocket receive public assistance to pay their premiums. Another big distinction Germany has is their cultural affirmation of safety-nets. They believe strongly, as a part of their culture, to take care of the disadvantaged because they acknowledge and accept the fact that anyone can fall into a disadvantaged state at any time. Professor Karl Lauterbach, a member of the German parliament, describes it as "a system where the rich pay for the poor and where the ill are covered by the healthy. It’s a social support system that is highly accepted by the population." They don't argue politically over whether or not to include a safety net, because they accept its necessity and that healthcare is a right to all. It is no surprise then that Germany has a higher life expectancy and lower infant mortality rate than we do. Single-payer, government-sponsored plans not only promise universal access, but also basic and essential benefits for every American. Some ways of approaching this can include a lot of government control, others can still include private insurers. The unfortunate circumstance in the great American healthcare debate is that our policymakers are fighting about how to take away care from the poor because they can’t pay for it. Instead, the overall goal should be to increase coverage and make it a public right for everyone. We can debate about how we do it during elections and in congressional conversations. Until then, I am calling for all politicians who are representing the people of the United States this 2020 election season to take a unified and bi-partisan approach to Universal Health Coverage and debate about the funding mechanisms and how we should do it, instead of fighting about whether or not we should. This is one opportunity where we can actually unite and get something meaningful done. Our elected policymakers must decide how much they value investments in our personal and community health. Remember, we are not isolated beings, we live in society with others, therefore an investment in one, is an investment in all. The closest thing to single-payer already working and established in the United States is Medicare, which is where the concept of Medicare-for-all comes from. The infrastructure is already built so it saves time and subsequently our taxpayer dollars. Medicare was established in 1965 to provide health insurance to all people age sixty-five and older, regardless of income or medical history. This is in direct alignment with the goal of the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights of 1948. Since then, all other developed nations of the world, besides us, have implemented some form of Universal Healthcare for all of their citizens. Instead the United States only declared this human right for anyone over the age of sixty-five. No one else. The program was expanded many times in the past to include people under age sixty-five; those with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in 1972 and in 2001 for those with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig’s disease). We seem capable of expanding coverage for those who are really sick, but not those who are poor. Medicare eligibility can further be expanded to help all people. Everyone who is working already pays for Medicare in their payroll taxes. This can be changed to be paid once a year during tax time. Options are available. It is often argued that Medicare-for-all would make us bankrupt and broke. What people often are missing is that although taxes will increase, our out-of-pocket monthly premiums will be eliminated. Forbes reports that “for the country as a whole this would largely be a financial wash.” This is in addition to what was noted earlier as well; we are already paying a whole lot more than other countries are paying for universal coverage and wasting money away too in efficiencies. Some form of Medicare expansion will not bankrupt us. The money to do it is already in the system. Yes, it will stop corporations from profiting off of us, which will make them upset of course, and as a result are the biggest opponents of Medicare expansions. The trade-offs of Medicare-for-all will take time, but what will happen with better efficiencies and usage of taxpayer dollars. I'm already paying $700 a month for a health policy through my employer that gives it to Aetna for me. I'd rather send my money to a federal system that will not profit off of me. Single-payer systems like Medicare-for-all will not be perfect, but will solve some of our fiscal and ethical dilemmas because it would be controlled by a government entity with public oversight and not a giant corporation that does not have our best interests in mind. Isn’t that the purpose of electing our politicians and having a government—so they can represent our best interests? At least that was the point of our founding Constitution. We could also keep private insurers and expand Medicare to all through the use of Medicare Advantage plans which are already developed, effective, and working. These are private insurance plans offered to Medicare beneficiaries that include additional coverage not covered by traditional Medicare. Private insurance plans that offer Medicare Advantage must compete with one another for Medicare's business which takes a market-oriented approach to competition and pricing. The Affordable Care Act put some regulations in place that required private insurance companies offering these plans to follow in order to help contain costs and maintain solvency—all in the interest of its beneficiaries (all of us who pay into the system for many years). Medicare Advantage plans are the managed care of Medicaid, except with regulation. State Medicaid managed care plans are not Federally regulated, which is why they are very inefficient, expensive, and full of moral abuses. A study published in Health Affairs found that Medicare Advantage plans, with the Federal regulation it has, costs less and delivers higher quality care than traditional Medicare. We can work out a deal with private insurance companies that wins for all stakeholders. Additionally, we get more choice, get the right to health, get to be one of several hundred million potential voters to help shape its structure, and become the true customer of American healthcare. This last component is extremely important because anyone under the age of sixty-five that has private health insurance is not the true customer in American healthcare. Large and small group employers are. Insurance companies don't sell to us, their plans are developed and designed and marketed to the needs of employers. Not consumers. Medicare Advantage plans are the only health plans, other than ones on the State Marketplaces and sold through brokers, that are targeted and developed for the individual. In an era of disruption, innovation, and entrepreneurship, health plans that are focused on individuals will evolve and be designed to accommodate individual needs. What we demand and want in healthcare will naturally arise from consumer demand when the individual is the customer. As health plans get disrupted, so will our providers who will regain autonomy and provide services for us that are designed to work the best for us, not designed so they are reimbursed the most by insurance. Expanding Medicaid coverage works too, but there are too many problems with the system because of its complexity between Federal, State, and managed care. If this complex system is simplified by getting rid of State regulation and moving toward standardized Federal regulation, then expanding Medicaid coverage through various programs such as buy-ins can work in the same fashion. But why keep young and the old citizens separate? Why have Medicaid for under sixty-five and Medicare for over sixty-five? It actually makes more sense to combine the two into one system for all the complexity reasons stated earlier, but also because it allows the older to spread their risk amongst everyone, including the much, much younger. In the same fashion as how large employer group plans are cheaper because they can spread the risk more, we can spread the risk amongst everyone in the country. Instead, we currently spread the risk amongst the poor (Medicaid) and the elderly (Medicare) in separate risk pools and wonder why we can’t control costs? I want to end by briefly touching upon the understanding that single-payer or Medicare-for-all programs will force physicians and other providers to take the biggest hit initially. However, providers have directly influenced our current situation and how we reimburse them needs to evolve. The fee-for-service reimbursement mechanism has pushed providers into a quantity-based mindset, which is why they see us for the short periods of times that they do. The Physicians Foundation surveyed U.S. doctors and found that about 40% see eleven to twenty patients per day and 27% see twenty to thirty a day. A forum of nurses note that they attend to an average of eighteen colonoscopies a day. We will no doubt have better health outcomes if our providers spend more quality time and interest in our health, instead of viewing us as items on a factory belt. Currently the system is not set up for the right incentives. We often look to doctors as if they are god's, without fault, but there is a reason why medical mistakes persists as the number three killer in the US—third only to heart disease and cancer. Providers need a serious reality check, and perhaps taking smaller salaries because what they provide is a public good and right to humans, should be considered. Absolutely, we should reform medical school tuition to help with this situation, but doctors have a duty to their fellow humans and maybe we need more ethical doctors who follow the oaths they take in medical school. Physicians that have high quality scores and do well with their patients, just like any other business, will succeed and do just fine. We want the low-performing doctors that have high complication rates to stop getting paid the same as doctors with high quality scores, and instead, go out of business. Remember the old adage “What do you call the person that graduates lowest in their class from Medical School? Doctor.” We as consumers are the only ones who can provide the guidance to our legislators on how to change the approach. Providers have been insulated from this market-based competition, and maybe that's exactly what they need. Change is what we need. Let’s start asking for it. Begin to take power back and become an informed health consumer. Share this with somebody you care about. I usually share this quote by writer and blogger Ian Welsh with my students at the beginning of all the healthcare ethics courses I've taught: “Morals are how you treat people you know. Ethics are how you treat people you don’t know.” This is a powerful way to frame the idea of values and how we interact with society. The personal values that we develop as a result of experiencing life creates the foundation for making decisions, guiding behavior, and establishing priorities. Twentieth century philosopher Lawrence Kohlberg devised a theory about how one becomes an ethical person. He called it Stages of Moral Development and concluded that people must go through one stage of development at a time before moving on to the next and that we move through these six stages as we find solutions to the challenges we face in life. Therefore, some people are unable to make certain decisions because of their ethical maturity. Even though someone is an adult physically, they can be morally immature based on the challenges they've been through and how they responded to them. The first two stages in Kohlberg’s theory are called Premoral, or before moral reasoning. Stage three and four are Externally Controlled Morals, or rules of society and culture. Most people remain on these levels. Stage five and six are called Principled Morals, or rules of a higher authority. These include making decisions with the thought that everyone is entitled to common rights. A respect for yourself and tolerance for others requires complex thinking about how you relate with others going beyond what is law. This is believing that all humans have worth and value regardless of their social status. For example, segregation at one time was legal, however, it was unethical and violated a higher law. Only 25% of the population actually gets to these last levels of highest ethical development and maturity. If our experience helps shape our morals, then we need experiences. People without kids do not truly understand people who have kids. The same goes for people with pets, or for people who have lost a child to gun violence. How can we truly feel empathy for somebody in a certain situation until we experience it on our own? Consider the following: How can people who have never been uninsured have empathy for somebody who has lived with no insurance? Can a politician that has never been without insurance advocate for single-payer system that includes all? Will the CEO of an insurance company make decisions to reduce premiums, if she never suffered personal bankruptcy due to health care expenses? Can a man that has never been sexually advanced, groped, molested, or raped develop policies effectively for a woman who has? Yes, it is possible. People with higher ethical maturity levels have the ability to do these things. These types of people, I argue, are the kind of leaders we need making decisions in healthcare. If one wants to buy a Mercedes they can go to a car dealer, pick a color, arrange financing, and have a new car. If one can't afford to buy a Mercedes then maybe they will leave the Mercedes dealer and pursue a Ford Focus or decide to just stick with riding the bus. Either way, you the consumer is in charge of that purchase. Mercedes isn't responsible or under obligation if one cannot secure financing or afford the car with cash. The luxury car maker has no ethical duty. Although healthcare is a business it has very different financial obligations than other industries within our economy. People do not want to purchase cancer treatments, chronic disease remedies, asthma inhalers, or request hip surgery. In the United States health care consumers are not in control of most health purchases outside of the retail market. This comes from the fact that consumers do not manage their healthcare dollars, instead, they send their premiums to an insurance plan that makes most decisions for them. Most health care consumers don't really understand their bills and can't tell you how much their products and services cost them. Health consumers know premiums, deductibles, and co-payments, which are the entry fees into the United States health system. Their choice and role in purchasing is minimal. As a result, we cannot treat healthcare like any other industry in the free market. A healthcare system cannot function without the boundaries of duty and obligation like Mercedes can. However, the reality for Americans is that we are operating outside of those boundaries in a system without duty to the human being. American healthcare is a commodity treated like any other industry within the market economy and is not managed like a human right. In 1948 the United States signed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights which included equal rights to adequate health and health care for nation citizens as a public good. As of today, this makes the United States the only industrialized and developed nation that hasn't secured health care as a public right for its citizens. Since someone else takes care of our healthcare dollars, and these healthcare resources are limited, using them must be done in a responsible way. The balance of profit and social justice is a true dilemma in our healthcare system, but is it not impossible to balance that scale. If leaders of an organization are motivated by money, it can deter the mission of caring for the sick and injured, promoting prevention, and keeping people healthy and happy. Fiscal responsibility is a duty to be responsible and accountable with money, especially someone else's, and is a marriage of numbers and values. Therefore, an organization's financial statement is their ethical statement. This is because what an organization prioritizes and spends their money on defines what's important to them. One of the biggest issues we have in the United States healthcare system is not having enough money for health care, but it is how that money is spent. Check out the salaries below of top health industry executives and consider what their organizations prioritize and what their values are: Nearly all large healthcare organizations make their top executives extremely rich. A perverse incentive to profit off the sick. Sarah Anderson, Global Economy Director at the Institute for Policy Studies said "If executives are loaded up with stock options and other types of equity-based pay, they have a personal incentive to boost shares prices by whatever means necessary.” One top earner is CEO Martine Rothblatt of the pharmaceutical company United Therapeutics who took home $37 million in 2018. United Therapeutics makes drugs to treat high blood pressure and for pediatrics with high-risk cancers. For comparison purposes, Seema Verma the CMS administrator who oversees Medicaid and Medicare is given $165,000 in salary paid by tax dollars. If CMS administrators were getting paid $5 million dollars with tax money there would be upheaval about how our tax money is spent. How come we don’t question how our other healthcare dollars are spent? Where do you think these executives fall within Kohlberg’s ethical maturity levels? In the current environment of 30 million people uninsured, and millions of others having high deductibles they can't afford, do you think it's acceptable for these types of compensations? Is it justified or fair that health CEOs took home 11% more of our money on average every year since 2010 according to an Axios analysis. What are the priorities of these executives when they take such high salaries? Is this fiscally responsible with our limited shared resources? Welcome to the executive compensation problem that exists in the United States. Other countries don't seem to have the same CEO compensation problem that we do. How big of an ego does the United States have? Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development theory notes that it is possible for people to be unable to make certain decisions because of their ethical maturity. This provides an explanation for how healthcare executives can take home salaries of multi-millions of dollars amidst all the challenges the health system currently has; people are unable to afford to get a necessary surgery, procedure, or medication because their deductibles are too high, every six minutes a patient dies in an American hospital from a hospital-acquired infection, preventable hospital errors persist as the number three killer in the US–third only to heart disease and cancer, and on average a hospital patient is subject to one medication error per day. Large corporations and CEOs will argue that these wages are necessary to attract the best and brightest executives to the healthcare industry. How is it that our executive health leaders think they deserve such pay when our system is in shambles? For most other people in the corporate world bonuses and raises are based on performance and hitting targets and goals. I can't imagine we are hitting targets and goals with the current state of our health system. Or maybe the targets and goals should change? CEO Wayne Smith of Community Health Systems had received $16 million dollars in total compensation yet recently settled a lawsuit alleging false billing and kickback allegations, both federal crimes. If our system was booming with better health outcomes, affordable coverage, less fraud, and no uninsured, then perhaps it would be justified to have executives taking such high pay. Further, if we treat healthcare as a right, or like most countries do as any other public service like the library or police, then our current system functions without morals (or pre-moral stage one-two) also known as immoral. If leaders in healthcare had a stage five or six ethical maturity level (principled morals of a higher authority) do you think they would take salaries such as these? It is hard to argue that these executive leaders are ethically mature.

Healthcare isn’t Pepsi, Coach, Kellogg, Hilton, Koehler, or Mercedes. People don't need to drink Pepsi, wear Coach bags, eat corn flakes, or stay at hotels to survive, but they do need access to healthcare for optimal health and wellness. Leaders in healthcare must have different values than leaders in other industries within the shared economy because of this striking truth. To put this into perspective let's examine the scenarios of CEOs taking a pay cut:

The opportunities are endless in what health executives can do with our health dollars instead of high salaries for themselves and the rest of their executive c-suite team: lowering of deductibles and copayments, adding additional coverage such as functional medicine, holistic practitioners, more psychotherapy sessions, coverage for massages, provide free or low -cost services/programs/screenings, or increases in salaries for workers. What is it that organizations are willing to give up to take on a large multi-million-dollar salaries for their executive teams? Again, an organization’s financial statement is their ethics statement. Do you think they are acting with social and fiscal responsibility? Specifically for pharmaceutical companies where executive compensation is higher than most health sectors, consumers do not directly feel the pain of the high costs of prescription drugs. This is because the costs are in co-pays which are set fees we can expect. These high costs are filtered through the system and hidden as higher premiums and deductibles because our insurance companies pay the rest of the bill for us with our premium dollars. We are not only paying for the drug itself, but also supporting a $66 million-dollar salary for its CEO. In 2017 healthcare reporter Bob Herman published an analysis of the salaries of over one-hundred CEOs of seventy of the largest U.S. healthcare companies since 2010 based on corporate financial filings and cumulatively these CEOs have earned $9.8 billion. Imagine the magnitude of those dollars and how they could be spent differently within our system. The Institute for Policy Studies note that $75 million is the equivalent of the cost of dental insurance for 250,000 Americans or the average annual health insurance plan deductible for 24,000 people. That is just a small fraction of that $9.8 billion. Even more, consider the cumulative cost of the rest of the c-suite that get similar salaries: CFO, CEO COO, CIO. An analysis done by Modern Healthcare noted that one company alone, Health Care Service Corp., the Blue Cross and Blue Shield insurer in five states, paid the top ten executives cumulatively $56.7 million in 2015. There are several familiar guiding principles of healthcare ethics such as doing no harm, preserving life, being discreet, upholding justice, and respecting autonomy. Health leaders will never be given enough resources to satisfy all the demands placed upon them by a community, but they can turn to the guiding principle of justice to help them distribute their yearly budgets ethically. Justice refers to fairness and equality and stems from a rather simple but complex ethical concept called the Philosophy of Individual Worth. It is a duty and moral obligation for health systems to give the same treatment to everyone regardless of one’s circumstances. Leaders in healthcare have a duty to go beyond personal feelings and honor the individual’s worth. I mean, really, we want the same don’t we—for people to respect our needs, what we want, and believe? But this is hard to do and as a result, leaders in healthcare must have this skill, which I argue is only possible by some with higher ethical maturity. Justice is also the fair distribution of benefits offered by a society and includes the fair distribution of its burdens as well. Society suffers injustice when not everyone gets to share in the benefits and when distributions of resources are not equal. In healthcare this creates an environment where health equity is compromised and health disparities shade society with injustice, which is the unfortunate reality in the United States. Since we live in a healthcare system where someone else takes care of our healthcare dollars, the concept of good financial stewardship and the duty to be fiscally responsible with limited healthcare resources is supported by the ethical principle of justice. Award-winning 20th century philosopher John Rawls was interested in what makes a just and moral society. He formulized a hypothetical theory where people are equal to each other and all humans have worth in the Original Position and if we take a Veil of Ignorance with each other a social contract would develop that secures basic rights for everyone and protect those in all positions of society. His theory goes on to say that the advantaged have a responsibility to the disadvantage. Those that are disadvantaged could include those in poverty, ones with chronic disease that affect the quality of life, the disabled, etc.. Therefore, in the end, it is in our ultimate best interest to do this because everyone has the potential to be in the lesser position (loss of job, health, etc). John Rawls said “a just society is a society that if you knew everything about it, you'd be willing to enter it in a random place.” Consider that powerful thought: are you willing to be born into a low-income, black family in Chicago? Statistically this population has the highest health disparities in the country, and as a result, end up in unhealthy situations that produce a symptom of another statistic; highest homicide rate. At the core of Rawls theory is that no matter what our circumstance, environment, or influence, we are human, and all human interests must be observed to truly live in a moral, ethical, and just society. This is not what our reality is today. Especially not in our health system. If we want people to be tolerant of our ideals, we must be tolerant of others. This is why the balancing scales are often the symbol used for justice. Only one set of ideals getting priority does not work. Executive compensation metrics are a powerful reflection of the priorities of an institution. While the general population complains about, and suffers from, the ever rising healthcare costs, no one is championing efforts for fiscal responsibility and transparency of the spending of our shared resources by executive leaders in healthcare. Instead, the general American population is unknowingly supporting executive leaders becoming very rich off of the sick and our limited healthcare dollars. We have evidence popping up every day in our society that the status quo is not working. Just as health leaders reduce the numbers of nurses on the floor that care for patients in order to save health dollars, maybe we should consider eliminating a few million dollars of executive pay instead. What do you think will positively impact patients more: fewer nurses or less executive pay? According to a JAMA study, there is no link between CEO pay and hospital quality indicators such as re-admission rates, mortality rates, or community outreach programs. In other words, a highly paid CEO will not necessarily increase the performance of a hospital and the outcomes of patients. Its unsettling that CEOs at hospitals with high mortality rates are being paid just as much, or sometimes more, than those at hospitals with lower rates of mortality. Physician compensation is increasingly being tied to quality measures and I argue that executives should be treated the same given that they have a fiduciary and ethical responsibility to represent the welfare of the community in which the serve. An analysis by Kaiser Health News found it was more common for executive bonuses to be tied to boosting volume rather than increasing quality, which unfortunately sets up an environment where the incentives are to keep people returning to the hospital, not preventing them from needing to be readmitted. With that, I am calling for policymakers, tax payers, and health consumers to consider new public policy to tackle the injustice of excessive executive pay that exists in the American health system. I am proposing a professional consideration of placing caps and limits on executive compensation in these fields. This is argued based on the fact that healthcare is something every human needs, and is an industry that all is born into, lives, and dies in, it simply cannot be employed in the same manner as a company that sells running shoes. The recommended process for determining the appropriate compensation usually is to conduct a review of what similarly-sized organizations in the same geography offer their senior leaders. However, since healthcare is not like any other industry due to its ethical duties and obligations, the same process simply cannot apply. A new way of calculating executive compensation must be developed so that precious and limited healthcare resources can be distributed fairly and used effectively. Until that happens, I am calling for health executives to make a progressive move and donate their excessive compensations back into the system. Does anyone have the guts? I believe wholeheartedly that ethically mature leaders in healthcare exist that are capable of making major healthcare business decisions without the multi-million-dollar salary to prove their worth and competency. The present chaos that exist within our healthcare system shows that the current model of excessive executive compensation is not working and immoral. Begin to take power back and become an informed health consumer. Share this with somebody you care about. This piece was written in response to the editorial article Obamacare has a fever coming on published November 23rd, 2015 in the Chicago Tribune.

** It has been noted that health insurers are crying about the money they are losing in the Obamacare exchanges. It is only true ignorance that health insurers actually thought that more of the healthier people would sign up for insurance in the Obamacare state exchanges than those who did. The market in which it was intended to target are those who don’t have access to insurance through work or don’t qualify for Medicaid – traditionally, individuals who have always had a hard time getting health insurance, thus a decreased health status because of historically being uninsured or underinsured. Not sure how this is such a shock to leaders of health insurance companies, but ask any public health expert and they will tell you that people become healthier by having access to healthcare, or in this country, by having insurance. In response to losing money on the health exchanges, many health insurers have increased premiums, reduced networks, got rid of popular plans, and continued with high deductibles. They are doing exactly what they were doing preACA – pricing individual plans out of affordability. This is the exact issue the ACA’s exchanges were trying to fix. That status quo, however, is continuing, that is, the same thing that didn’t work before. The agenda for those with this type of thinking is partially to ruin the ACA’s progress with health reform, and instead, keep the status quo which has thus far led us to the inefficient, costly, and poor quality healthcare system we currently have, including a nation full of many uninsured. Things we should be ashamed of as the richest country in the world. It’s imperative to continue this conversation in the same manner as we did with ERISA, COBRA, HIPAA, and then the ACA in addressing the abuses by insurers. We have been reforming health insurance abuses since the 1970’s with the introduction of these laws and have been carried over plenty of times and evolved into what we have the with ACA. We must keep evolving. Change needs to happen, and we cannot go backwards to where we were—we need to move forward and continue to progress. So how do we continue the conversation? It’s inherent and required that we start looking with a different perspective. Taking away benefits will never work as the essential health benefits are necessary to moving away from underinsured, or people having subpar plans that do not cover what a human being needs – thus the rigid requirements of the law, since insurance companies were not providing these out of their general kindness or support for social responsibility. And yes, Mental Health is a benefit that people need, as well as Massage Therapy. But that’s an argument for another article. When organizations want to keep people from having insurance and go out of their way to remove them from the system with exclusivity through high costs, we’re not only widening the gap between the rich and the poor, but also keeping people unhealthy and populations of unhealthy people make even more people unhealthy. The system forces these individuals to avoid doctor’s visits and routine checkups because of high deductibles and other fees. Nonetheless, there are leaders in healthcare who want to keep people unhealthy, and I am only led to one rational conclusion: they want to keep us sick. Many of us agree that healthcare has many issues that need fixing. As a life-long consumer, researcher, and employee in healthcare, I have come to the deduction that the issue plaguing the entire system is due to one thing—treating healthcare as a commodity. Everything boils down to managing healthcare like it is any other business. But healthcare is not boots we put on our feet or cologne we spray on our bodies but instead, our daily quality of life we are buying. What has been lost is the fact that healthcare is a very different industry than the others in the market, and we shouldn’t even try to make money from people using healthcare as needed. When treating healthcare like a commodity instead of a right, it changes how decisions are made and ultimately how it functions. The thinking that individual plans were not profitable for health insurers is right along the lines of this type of thinking - and we need to move away from it for true sustainability. Healthcare shouldn’t be played in the market like the others, but instead looked upon as the foundation that allows the others to be played, because people need to be healthy for any real economy to thrive—or in reality, any living system. Perhaps the actual root cause to the bubble bursts in our economy from various sectors are truly due to the health of its consumers. Everyone who has access to healthcare is a healthier consumer. One bold perspective is to give more benefits to get people healthier, instead of restricting or reducing access and coverage. This concept brings us back to the beginnings of health insurance, when Henry Kaiser wanted to ensure his employees stayed healthy and out of the hospital, an experiment of his that proved to be beneficial. An example of this is giving more mental health benefits to better manage chronic health and ultimately lower costs as the comorbidity of chronic disease and mental health is very high. Such coverage could cut costs by keeping patients out of emergency rooms and potentially ward away serious health problems that ultimately cost money—and make people unhealthy. Or even bolder, health plan leaders making sure that individuals have access to truly affordable plans to make them healthier, and eventually down the line, even save them costs from reduced claims. This is truly a win-win, yet bold moves are not what the status quo likes. Incumbents are not ready because they can adjust their priorities to provide health plans that are affordable, they just don’t want to. Healthcare consumers must wake up and start giving health insurers the pressure they need to make changes and provide more value. Right now, leaders in health insurance are comfortably raising our premiums every year as they collect millions of dollars in salary. McKinsey & Co. estimated that insurers lost $2.5 billion on Marketplace policies in 2014, but we must be reminded that CEOs from ten health insurers took $1 billion in compensation alone in 2014. This doesn’t include the rest of the executive team and other insurance companies. The average CEO pay has reached nearly $10 million a year per company, with some at the heights of $25 million. Let’s also be sure to include into this conversation retirement packages, such as the package CIGNA CEO Edward Hanway received when he got the usual salary that year but also gave himself a $111 million pension package as a going-away gift. This is what our healthcare dollars taken monthly or biweekly from our checks and bank accounts are partially supporting—people getting super rich off sick people. It’s difficult to take health insurers seriously when they cry about losing money with their exchange plans when this type of greed exists within their leadership structures. We need to turn the conversation: what’s the priority; do we want to get people healthy and give them insurance, or do we want to continue treating healthcare as a commodity and restricting people from the basics they need to live a healthy life? This election year—voters should decide. Late Canadian politician Tommy Douglas said it perfectly, “People are more important than profits.” But this type of thinking doesn’t exist in leaders of health organizations in the U.S. because social responsibility doesn’t seem to come easy for incumbents, and they keep the political system working in their favor through the high salaries that they receive. It’s a vicious cycle and in the end, it’s U.S. citizens that are ultimately hurting. A less known provision of the ACA, section 9014, sets strict limits on how much health insurers can deduct off their federal income taxes for the expense of executive compensation. It was no wonder why so many of them wanted the ACA repealed, but this provision exists for a reason as it is designed to limit excessive executive pay in a time when healthcare costs are sky-high. According to a report by the Institute of Policy Studies, these new deductibility limits generated $72 million in additional public revenue in 2013 from America’s largest publicly-held health insurance companies. This $72 million is the equivalent of the average annual health insurance plan deductible for 28,000 people. It’s obvious that continued reform in healthcare is needed, very few argue against that. As a developed nation that has the money, power, and influence to change our current system for the better—we can and have the capabilities and maybe more importantly the responsibility. I believe it needs to begin with looking at healthcare as a right and not a commodity. The basic guarantee of access to healthcare for individuals has a chance to be saved if we have a serious reality check. We cannot go back to allowing health insurers to tailor their offerings to the varying needs of people in the market, but instead by putting caps on salaries and providing adequate policies that people need through making social responsibility a priority. The CEO compensation problem that exists in the U.S. needs to be removed from the healthcare industry as it has directly led to the fiscal irresponsibility that is driving costs to $700 billion more a year than we need to, as study after study has shown. People are perfectly competent enough to run successful companies without getting multi-million dollar salaries. I challenge health insurers to be bold and try something new. Have the guts to take a stand for better health and push the Darwinian energies in your favor, as the bubble will continue to bloat and will burst if we go back to the pre-ACA times. I challenge insurers to be transformative, as evolving is truly what makes companies fit. Because if insurers don’t, they will capsize just like the 12 of the 23 state health co-ops and be replaced by modern technology and thought. This is the cyclical nature of all things, including business, and how markets thrive and grow. This is business school 101. The reality check is that health insurers need to evolve or become extinct. I do have hope, that naïve American spirit, that eventually either an organization or leader will succeed in making healthcare a right in the United States. Chicago is home to entrepreneurs of all types, including technology in healthcare. Innovation is being discussed and tested, such as automated health insurance based on just the demographics that need to be considered automating the actuary process—the opportunities are abundant. Successful experiments like Accountable Care Organizations could potentially replace health insurers all together. Entrepreneurial ventures like Uber and Lyft have changed the game for transit and are competing directly with Taxi Cabs in the same fashion. Health care consumers will catch on; entrepreneurs will be successful, and the smart tech savvy millennials are connected and are constantly sharing information with each other. The entire concept of health insurance needs to change or the pressure will mount at some point. Change scares people—especially paradigm shifting change—and it’s here. |

Kat LahrResearcher, Writer, Educator, Reformer & Believer of Health Care as a Right Archives

April 2020

|

|

CREATING AWARENESS IN

HEALTH CONSUMERS |

TC Publishing |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed